Dispirit of ’76

On history’s echoes, broken promises, and why I’m still trying to believe in a beautiful world.

I’m driving my snazzy Ford Mustang electric car through the early morning haze of a thus-far soggy Missouri summer, sipping green juice from a portable Ninja tumbler, listening to a podcast that toggles between stoic philosophy, tech stocks and the benefits of magnesium. My cabin is cool, the traffic uncharacteristically light. It’s a kind of calm satisfaction that, for me, would’ve been hard to imagine even ten years ago. The technology, the comfort, the options—they’re all here.

And yet, out the window, I pass a patchwork of contradictions: American flags draped next to “No Kings” banners, while others fly the name of a single man, some in devotion, others in defiance. It’s not a quiet patriotism anymore. It’s loud, aggressive, and weirdly merchandised.

In that strange blend of freedom and fury, I’m reminded again: we as a nation have remarkably good aim when it comes to shooting ourselves in the foot.

Still, I’m trying to find optimism.

That’s where Donald Fagen’s 1982 song “I.G.Y.” comes in—a rare turn toward hope from the co-founder of Steely Dan, a band not exactly known for sentimentality. The title stands for the International Geophysical Year, a real event from 1957–58 when Cold War rivals briefly dropped their guard to collaborate on science.

Fagen’s lyrics channel the gleaming futurism of that era, painting a world where machines glide silently, cities run on solar power, and “by ’76, we’ll be A-OK.”

It’s easy to assume he’s being ironic, and to some extent, he is.

But there’s also something else: a wistful belief that the promise of technology, coupled with human cooperation, could produce a beautiful world. A glorious time to be free. Even if that vision was naive, even if it didn’t account for the politics, inequality and human nature that always gum up the gears, there’s still power in the dream.

And maybe we need that dream more than ever.

The Many Faces of ’76

Every American century has its own version of ’76: each one a mirror, or maybe a funhouse reflection, of that original declaration in Philadelphia. These are years that ask who we are, what we stand for, and how close we’ve come to the ideals we celebrate every Fourth of July.

1776, of course, was our nation’s bold prototype. Equal parts Enlightenment manifesto and high-stakes gamble. It gave us fireworks, stirring language and a founding myth we’ve been revising ever since.

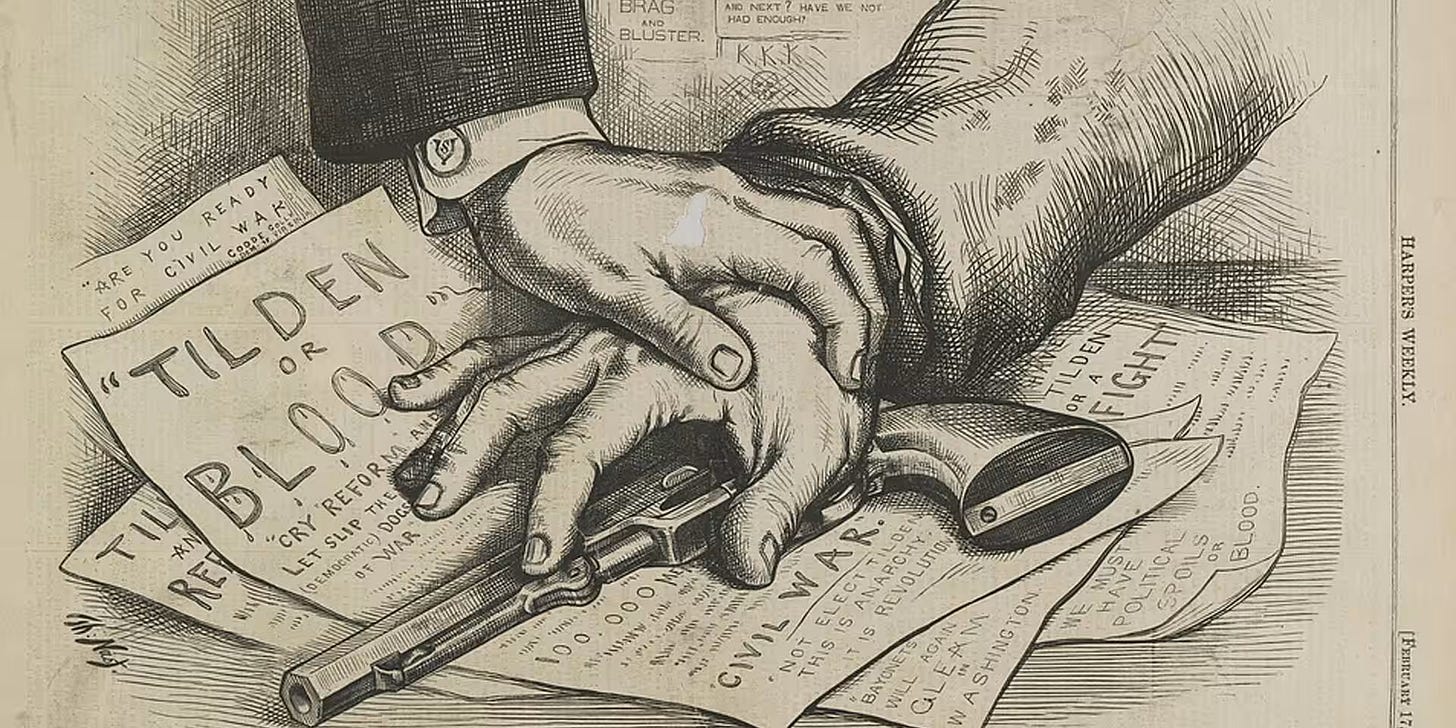

1876? That one cuts deeper. A hundred years after declaring independence, the country was still reeling from the Civil War. Reconstruction was crumbling, and a fiercely contested presidential election would be resolved not at the ballot box but in a closed-door compromise that effectively ended federal efforts to protect the rights of newly freed Black Americans.

That bruising election between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel Tilden remains, by most serious historical accounts, the most corrupt and cynical in American history.

Tilden won the popular vote, but the results in several Southern states were marred by violence, intimidation, and outright fraud. The eventual deal—known as the Compromise of 1877—handed Hayes the presidency in exchange for withdrawing federal troops from the South, thereby abandoning Reconstruction and greenlighting the Jim Crow era.

Modern partisans sometimes try to claim the mantle of “most corrupt election ever” for more recent contests. But that’s mostly performative outrage, unmoored from historical fact. If 1876 doesn’t top the list, then the list itself is suspect.

It’s also the setting for one of my favorite novels: 1876 by Gore Vidal. The book is a biting, elegant satire that skewers Gilded Age politics and doesn’t spare one of my personal heroes, Ulysses S. Grant.

As President, Grant was—let’s be charitable—a bit hapless at times. His administration was marred by scandal and mismanagement. But I still believe he was, at heart, a good man. A reluctant politician, a brilliant general, and someone who truly believed in the postwar vision of an integrated, freer America. Vidal, being Vidal, took him to task with his usual surgical flair. And maybe that’s fair.

Being a good man doesn’t always mean being a great president.

1976 was supposed to be a moment of national renewal. The Bicentennial came wrapped in flags, red-white-and-blue bunting, and the kind of manufactured optimism you only get when a country’s trying really hard not to talk about Vietnam, Watergate, or economic stagnation. We got parades, tall ships in the harbor, and an attempt to feel good again. It was a vibe—but not quite a revival.

In 1876, Gore Vidal gives his narrator, Charles Schermerhorn Schuyler, a line that has only gained voltage with time:

“But then Americans have always lived entirely in the present, and this generation is no different from mine except that now there is more of a past for them to ignore.”

It lands like a shrug and a slap.

And it also explains a lot.

The erosion of institutional memory, the flattening of civic history, the utter allergy to complexity—none of it is new. But the stakes feel higher now. What’s most troubling is how many people reject even modest historical comparisons not out of principle, but out of reflexive denial. A denial rooted in myth, in ahistorical comfort, and in a kind of childlike refusal to grapple with what this country really is—and always has been.

We’re technologically ahead of schedule and spiritually behind. The dreams of 1950s futurism came true in strange ways—self-driving cars, high-speed connectivity, artificial intelligence that both fascinates and hallucinates—but the political atmosphere feels more 1876 than 1776.

There’s tension in the air. Distrust. People staking out ground not just with bumper stickers, but with flags that declare allegiance not to the Constitution, but to individuals.

Each ’76 presents a version of America: the ideal, the reckoning, the reinvention. And maybe now, we’re being called to decide which version we want to carry forward.

An Empire Remembering Itself

Because here we are, approaching another Independence Day, and it’s hard not to feel like the republic is running on fumes. Our current leadership seems less interested in governing than in settling old scores.

Entire policy agendas appear animated not by vision, but by grievance. We’ve become, as I said earlier, remarkably good at shooting ourselves in the foot—and now we do it for applause.

This is where I find myself missing Gore Vidal’s salty voice more than ever.

Vidal had no illusions. He saw America not just as a flawed democracy, but as a fully functioning empire—one that, in his view, took its final wrong turn when Harry Truman signed the National Security Act of 1947. That legislation created the CIA, the Department of Defense, and the National Security Council, effectively institutionalizing a permanent war footing and ushering in what Vidal would call the “National Security State.” It marked, to his mind, the moment when the republic became an empire with global interests and little regard for domestic consequences.

And yet, Vidal loved the architecture of America; its secular ideals, its republican foundations, its capacity for reinvention. What enraged him wasn’t the country’s founding, but how subsequent generations so often failed to understand what a fragile, extraordinary thing had been handed to them. Or worse, how willing they were to give it away for convenience, comfort, or cheap theatrics.

He didn’t write off the country. He tried to wake it up.

And that’s where I find myself today: not hopeless, but haunted by potential. Haunted by the disconnect between what we are and what we could still be. America as empire is no longer just an abstraction. It’s visible in our posture, our politics, our refusal to govern ourselves with the humility the republic was built to require.

A Dare from the Past

Maybe that’s what this Fourth of July needs: less uncritical celebration, more critical memory. Less bombast, more introspection. Less cosplay patriotism, more actual participation.

Because history doesn’t end. It loops. And the America we get in 2026 may depend on whether we treat this moment as another ’76 worth rising to or just another one to survive and forget.

I think about this more and more on these early morning, hour-plus long commutes. My green juice is gone, replaced by lightly sweetened coffee still hot in a stainless steel Yeti. Another reminder that, in many ways, technology really has made the simple things better. I cruise down the interstate, then onto a state highway built by people who believed in the idea of physically connecting America—back when infrastructure was a national project, not a partisan punchline.

As I ride my silent electric steed, I notice the cracks—and not just in the pavement. Despite all the talk, and a valiant effort during an interregnum of thoughtful leadership, these roads are aging under the weight of neglect. Ironically, the roads built across the known world by the Roman Empire remain among the last enduring monuments to its greatness. Here in America, our infrastructure feels held together more by wishful thinking than by concrete.

The reminders of our own greatness aren’t cathedrals or aqueducts. They’re altered American flags, many festooned with AI-generated likenesses—many are faces that never served, never sacrificed, never sweated under the weight of the ideals this country was supposed to stand for. The blood, toil, and hard-won progress of generations gets smothered in polyester banners designed for outrage clicks and front-yard tribalism.

But the deeper fractures are social, institutional, and existential. We are a nation of people moving in different directions on crumbling roads that were meant to bring us together.

It’s hard not to feel like we’re stuck in a kind of national doom loop. We scroll, we react, we vote (maybe), and then we do it all again. We mistake performance for action, resentment for principle, and outrage for leadership. And while we’re busy reenacting the same old play, the window for people like me—Gen X, still trying to be useful—is closing. We had our chance to help steer when the Boomers occasionally stepped aside, and while we did some good, I worry it wasn’t enough.

Still, I think about my daughter and the world she’ll inherit. And despite everything, I want her to believe in that “beautiful world” Fagen sang about. Not because it was promised, but because it’s still possible. If we do the work. If we stay awake. If we resist detachment and lean into the messy, often maddening business of democracy.

Fagen’s chorus lands like a dare:

“What a beautiful world this’ll be / What a glorious time to be free.”

It's not a guarantee, it's not a punchline. It's just a vision; one that we still have the tools to build, if we choose to.

This Independence Day, maybe that’s the real challenge. Not just waving a tribalized flag or watching fireworks, but imagining what that beautiful world could still look like.

And then doing the hard, unglamorous, deeply American work of trying, however imperfectly, to build it.

Thank you! A lot to unpack. My own Fourth, more and more, is a time for reflection rather than bunting and fireworks, and this is a great start.

Have a great weekend!

It’s a weird 4th. I am torn with my feelings for our Country. Excellent article. Have a safe & happy weekend.